(NB This article is adapted from an article that appeared in Collectors Weekly about six months ago...I accidentally came across it and found it so thought provoking I had to share. I know these events happened years ago and things are different now, but many of us have memories of relatives who spent time in places like 'Willard'; and more importantly many of us have been through times when we could have ended up in similar situations if we'd been born a generation earlier. Thank you for taking the time to read this piece and to share your thoughts with me.)

If you were committed to a psychiatric institution, unsure if you’d ever return to the life you knew before, what would you take with you? That sobering question hovers like an apparition over each of the Willard Asylum suitcases. From the 1910s through the 1960s, many patients at the Willard Asylum for the Chronic Insane left suitcases behind when they passed away, with nobody to claim them. Upon the center’s closure in 1995, employees found hundreds of these time capsules stored in a locked attic. Working with the New York State Museum, former Willard staffers were able to preserve the hidden cache of luggage as part of the museum’s permanent collection.

“There were many patients in these asylums who were probably not unlike friends you and I have now.”

Photographer Jon Crispin has long been drawn to the ghostly remains of abandoned psychiatric institutions. After learning of the Willard suitcases, Crispin sought the museum’s permission to document each case and its contents. Crispin’s photographs restore a bit of dignity to the individuals who spent their lives within Willard’s walls. Curiously, the identities of these patients are still concealed by the state of New York, denied even to living relatives. Each suitcase offers a glimpse into the life of a unique individual, living in an era when those with mental disorders and disabilities were not only stigmatized but also isolated from society.

CW: How did you come across this collection?

Jon Crispin: I’ve worked as a freelance photographer my whole life. In addition to doing work for clients, I’ve always kept my eye out for projects that interest me. In the ’80s, I came across some abandoned insane asylums in New York State, and thought, wow, I’d really like to get in these buildings and photograph them.So I applied for a grant from the New York State Council on the Arts, got it, and spent a couple of years photographing the interiors and exteriors of these buildings. When the psychiatric programs moved out and shut things down, they basically just closed the doors and walked away. They left all kinds of amazing objects inside these buildings, including patient records in leather-bound volumes.

In the mid-’90s, I heard that at Willard—one of the asylums in which I spent a lot of time photographing—the employees had saved all the patient suitcases that belonged to people who came to Willard and died there. Starting around 1910, they never threw them out.

“I don’t really care if they were psychotic; I care that this woman did beautiful needlework.”

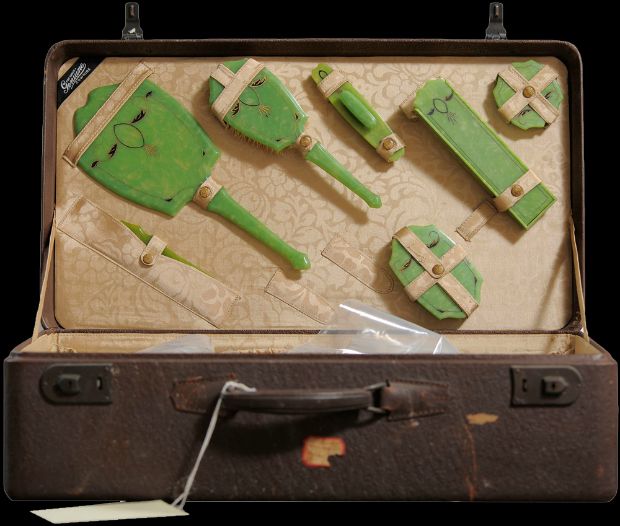

Clarissa’s suitcase.

CW: Do you think the patients had access to their suitcases after they arrived?

Crispin: There were many levels of mental illness in these places. Some people were in really bad shape, and sometimes had to be restrained, completely unable to function in any kind of society or environment. Those people probably did not have access to their suitcases.

“It wasn’t some hellhole where people were chained to the walls.”

But a large number of people at the asylum were ambulatory. They were out and about; they worked at the farm; they did artwork. Some of these places even had their own dance bands. The Utica State Hospital had a literary journal. There were many patients in these asylums who were probably not unlike friends you and I have now. The reasons why people were put in these facilities ranged from everything to serious psychoses and delusions to people who couldn’t get over the death of a parent or a spouse. Other people were institutionalized just because they were gay.

Freda’s suitcase.

Anna’s suitcase.

CW: Can each suitcase be traced to an individual patient?

Crispin: I have access to all the names, and New York State has the medical records for anyone admitted to these hospitals since the 1850s, so their histories are well-documented. I would like to use their full names in the photographs, but because of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), the laws about medical records and privacy, there’s some question as to whether or not I could be vulnerable to a lawsuit by the state.

Anna’s suitcase contained an inventory of her glamorous clothing.

Here’s a weird story: When I do the shooting, my digital photographs are labeled with what’s called IPTC information. It’s all the camera metadata stored with each photo, and you can add whatever you want. I typically add my copyright information, and also the names of the Willard patients for my own records. But when I upload photos to my blog, I strip that out.

For one person’s suitcase, I forgot to delete their name. Two days later, I got a call from someone who’s desperate, saying, “Do you have the objects of —?” and she gave the name of the person. And she said, “That is my grandmother. We didn’t know anything about her.” She had Googled her grandmother’s name and came across the Willard suitcases on my site. But even in this situation, the woman had to prove to the state that she was not only the granddaughter of this person, but that she was legally the recipient of her estate. So, in other words, if the grandmother had willed her estate to the other side of the family, this woman would not have been able to get access to her things.

One of Eleanor’s five storage containers.

I’m still trying to figure out how I can name these people, because I think it dehumanizes them even more not to. People who’ve been in mental institutions themselves have said, “Your project is very moving to me, but I’m very disappointed that you have to obscure names.” I think the stigma of mental illness has evolved from something shameful to something that’s much more medical and much more accepted. It just happens to people. But I’ve been very careful at this point in obscuring names, because there are many documents within the cases with names on them. I’m not showing their medical records; I’m only talking about the fact that they lived at Willard.

CW: Why weren’t these suitcases returned to family members when these people died?

Crispin: They tried, and again, the issue had to do with HIPAA laws. Contacting people with the information that their suitcases were in possession of the state was complicated by HIPAA. But the other problem was that a good number of these people were basically abandoned by their families, and their relatives showed very little interest in receiving their things after they died.

A detailed view of Eleanor’s sewing supplies.

CW: Was there any single suitcase that stuck with you?

Crispin: One of the last cases I shot was from a guy named Frank who was in the military. His story was particularly sad. He was a black man, and I later found out he was gay. He was eating in a diner and felt that the waiter or waitress disrespected him, and he just went nuts. He completely melted down, smashed some plates, and got arrested. His objects were particularly touching because he had a lot of photo booth pictures of himself and his friends. Frank looks very dapper, and there are all these beautiful women from the ’30s and ’40s in his little photo booth pictures. That really affected me.

Frank’s suitcase included much military-related ephemera.

Dmytre’s suitcase is another that I really like, it’s the last case I did. Dmytre was very moving. He was Ukrainian and clearly brilliant. He had notebooks filled with drawings of sine waves and mathematical things like that. There’s a wedding picture of Dmytre and his wife, and she’s holding a bouquet of fake flowers, which were also in the case.

Dmytre was interesting because he got arrested by the Secret Service because he went to Washington, D.C. and said that he was actually married to President Truman’s daughter, Margaret Truman. And what’s great is there’s a little Washington monument thermometer in the case, so clearly he bought a little tchotchke on his trip to D.C. and then later got arrested for saying that he was Margaret Truman’s husband.

Some of the objects in Frank’s suitcase.

Obviously, some of the cases were a lot more mundane than others. There was one that had syringes in it that were so beautiful and old, and small drug packets with pills still in them. There were combs, books, bibles, clocks, and an incredible Westclox Big Ben alarm clock in its original box that’s unbelievably pristine.

There was lots of expensive stuff, like perfume bottles from Paris that were worth tons of money. People wonder, how is it that a woman who’s committed to Willard has a bottle of perfume, which even at the time was super expensive? Mental illness doesn’t target any one particular group of people; it takes all kinds.

Dmytre’s suitcase contained his wedding photo and the flowers carried by his wife.

CW: Did stories often emerge from the objects you found inside each case?

Crispin: You could tell a lot about a person by what was in their case. One of the most touching letters I read was written to a woman who had been in another asylum and then released and finally sent to Willard. There was a letter from her sister, saying, “You could come back to Erie, but I don’t want you living in the YMCA because they’re still really upset with you for trying to stab that girl.” That one letter tells you a ton about what this woman’s life was like.

Souvenirs and scientific notes found in Dmytre’s suitcase.

But every case was different; I was constantly blown away. It was very important to me not to carelessly rifle through these things and forget that they were somebody’s personal belongings. And I really have a lot of respect for these people as well as the nurses and doctors who worked at the facility. I came away from all of this and the asylum work I did in the ’80s thinking that the state was actually trying to help people. It wasn’t some hellhole where people were chained to the walls. They tried to help, and I think it’s important to keep that in mind. While I was reverent, I tried not to be overly serious. I actually laughed a lot. If you’re ever around people in psych centers or even psychiatrists and nurses, a lot of their experiences are funny. Some of the items were amusing, but some made your heart ache, and others made you go, holy shit, what is this about? I was constantly affected by the items, and that’s my goal with photographs.

15 comments:

so many remebers and amazing old pieces!

Beauty, I invite you to my luisaviaroma giveaway with TWO WINNERS of Prada and Louboutin garments.

EVERYBODY DESERVES HIGH FASION.

www.malesclutch.blogspot.com

Haunting collection, darling!

xoxox,

CC

My mom was in and out of an institution such as this. She took me through the building and it was chilling to see the basement area. Anyway, I have her diaries that I simply can not bring myself to read. I wonder if the photographer found any diaries and what he did with them if he did find such. At any rate, as people too often fail to realize, the mentally ill are people too. Some have children even. Such tragic, sad, disenfranchised, and stigmatized lives they lead - even in this century. Thanks for this posting. I hope his work sheds some light and humanity on the mentally ill. They suffer both from their illnesses, often bad relationships with their families, and are also stigmatized and marginalized too. But, for the Grace of God, would go many of the rest of us.

Oh Lisa I understand why you can't bring yourself to read those diaries....one day maybe....or maybe not. So pleased your Mother had a family that loved her. Your compassion for all shines through in your words...

She was loving when she was not in the throes of a psychotic break. She also had tremendous empathy for others. I have a cousin who is ten years older than I am who wanted to read the diaries. I sent them on to her (I kept copies). My cousin thinks I should possibly never read them. Said she is having to take it a bit at a time herself. She is going to pass on the stuff I need to know. I am grateful to her. She also said that my mom wasn't half as crazy as people thought she was... The print shop lady who made the copies for me read part of it (she says inadvertently) and was surprised to read that my mom thought she knew who the Boston Strangler was. Well, my mom named the person as such. All so intriguing sounding and yet, I just think my brain doesn't need to know some things... Thanks for the post. Might just help someone else. Lots of people have these things in their families. Some just starting to learn how to cope with it.

After going over a number of the blog articles on your blog, I truly appreciate your way of writing a blog.

I book-marked it to my bookmark webpage list and will be checking back soon.

Please check out my web site as well and tell

me how you feel.

Here is my web page golden retriever lab mix breeders

I have to say that this article is Amazing !!! I have and it from the start to the end!!!! Absolutely Amazing! I love the to říše from Old Time :) Amazing post !!! More of them Please :)

Čem and see me an If you want we can follow each other ?:)

www.olivains.com

I really appreciate your writing and posts. This is so incredibly impacting; it makes me think so deeply about many issues and experiences,

This article and the photos really touched me-- I cried as I read it and looked closely at the photos (and I am not a "crier" by nature).

It breaks my heart to think that these patients were so alone that no one claimed their belongs and that HIPAA would stand in the way of returning the suitcases to loved one.

I appreciated the photographer took such great case with the suitcases too-- it's a way of protecting the patients dignity.

This post really blew me away.

ox jj

So touching. When things remain and people are gone, it always makes me cry. It should be the other way around. I remember when my mother died seeing her slippers a few days later and crying disconsolately. Pablo Neruda said it perfectly in his poem Las Alturas de Machu Pichu.

Thank you for always sharing such wonderful stories.

What an absolutely AMAZING article...

Sad, tragic, & interesting.

Packers And Movers Hyderabad to Bangalore

Packers And Movers Hyderabad to Ahmedabad

Packers And Movers Hyderabad to Jaipur

Post a Comment